This June, the Planning Institute of British Columbia (PIBC) announced 10 winners of its annual Awards for Excellence in Planning. The awards recognize outstanding professional planning work across British Columbia and Yukon, and five award categories reflect a diverse range of communities and practice areas.

The City of Quesnel and Urban Systems were honoured to receive a PIBC Gold Award for Excellence in Planning Practice for the Quesnel Waterfront Plan, a detailed vision for bringing the community of Quesnel closer to its riverfront spaces through inspired placemaking, cultural storytelling, and inclusive design. The award marks a years-long collaboration between Urban and the City which produced a plan celebrated for its ambition and creativity.

“We collectively created a vision that the community wants to see realized,” says Quesnel Mayor Bob Simpson of the plan. Located at the confluence of three rivers, the City of Quesnel has ties with the waterfront that are undeniable, from the thousands of years of pre-contact life along the river to the Cariboo Gold Rush, the forestry boom and the expansion of transportation networks within British Columbia.

“We often heard that Quesnel is that beautiful community up in the Cariboo that is nice to drive through,” says Mayor Simpson, “So we asked ourselves the questions: why would people come to Quesnel? How do we start to make the kinds of investments to enhance our strengths? And of course, one of our natural strengths is that we are on the confluence of the Quesnel River, Fraser River, and Baker Creek. We needed to find out how to become the River City that we are.”

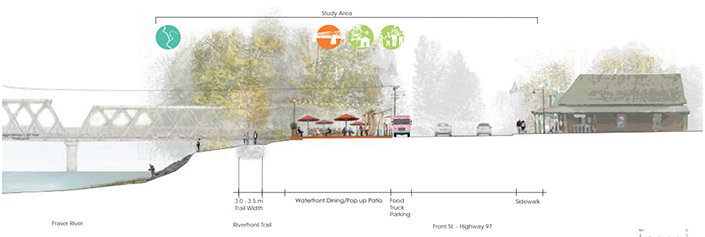

Urban was engaged by the City to lead the waterfront planning process, which examined eight kilometres of waterfront in the community’s core in order to develop a 20-year timeline of land use recommendations based on realistic economic development opportunities.

“The City recognized that the rivers are such a huge asset, and they are the things that have the potential to make people want to come to Quesnel and spend time in the community,” says Shasta McCoy, landscape architect and project leader. Shasta had already built a trusting relationship with Quesnel, collaborating with the community for the Reid Street Revitalization and Arena Precinct projects. Knowing the community’s built environment so well made the waterfront planning process more seamless for her and the team.

Along with Shasta, Urban’s project team included Catherine Berris, Maureen Savage and Lee Giddens from the landscape design practice; Chris Rempel, Jennifer Crosman and Alisa Khliestkova from the GIS team; Alyssa Crannis from the graphic design group; and David Bell and Andrew Cuthbert from the land economics practice.

Community feedback was gathered at nearly every stage of the waterfront planning project, including previous recommendations from the project’s supporting documents and policy contexts, such as the City’s Official Community Plan. The other engagement opportunities included four ‘walkshops’ with the public, a visioning session with Mayor and Council, an online survey, two private sessions with stakeholder groups, and a public charette of a draft Waterfront Plan.

“We wanted to be creative in how we asked people their thoughts, so Lee and I set up pop-up booths in the park, right on the Riverfront Trail.” Shasta says. This allowed everyday users of the waterfront to provide their input to the plan, whether they had planned to attend the booth or stumbled upon it accidentally.

“To me, that drove the conversation deeper in the community, and made the final product better, because people were physically there on the riverfront,” says Mayor Simpson. “It wasn’t just some theoretical exercise with a map.”

Invaluable feedback and insight came when the team was able to share the draft Plan with Lhtako Dene Nation, Nazko First Nations, and Quesnel Tillicum Society Native Friendship Centre, where they were invited to participate in an elder’s walk along the riverfront. Their perspectives informed the Plan at its core and reinforced a final design that promotes environmental stewardship, inclusivity, and celebration of Indigenous Peoples in the region.

“There’s an active awareness in the profession of landscape architecture to recognize the signs and realities of colonization in design. Because as settlers, we don’t always see the signs as clearly,” Shasta says. “So we communicated our intention of creating an inclusive waterfront, but it’s an ongoing conversation that doesn’t end with this plan. As each portion goes into detailed design, engagement with First Nations, and every type of user on these spaces, will inform how each phase comes together.”

After many months of analysis, engagement, and design, the final Quesnel Waterfront Plan was created. The result was a sophisticated visioning document, with a 20-year implementation framework and a bold set of design concepts.

“For me as a designer, it was a pure delight,” Shasta says. “I was really able to climb into a design space with all of the different districts, digging in and giving my best thoughts and attention to this project. I also felt that I was really able to design pieces in a more artistic way.”

Herself a stand-up paddleboard instructor, Shasta shared the City’s excitement for creating new experiences and destinations for Quesnel’s riverfront.

“We want people to have meaningful experiences with the water so that it ripples through their life and the decisions they make,” she says. “By having these connections, it leads to awareness to things like watershed protection, stormwater plans, and green infrastructure. The connection leads to awareness, which leads to action. These ideas shaped our design decisions.”

After the community enthusiastically received the final Plan, it was adopted by Quesnel City Council in December 2019.

Today, Mayor Simpson and the City of Quesnel remain committed and inspired to deliver the Waterfront Plan to the community.

“We are all-in,” says Mayor Simpson. “We have already moved into discrete design and planning phases on a number of these projects, with a view that we will receive grant funding for several more initiatives soon. It is not our intent to allow this Plan to sit on the shelf.”

After hearing that the project earned a PIBC Gold award, Mayor Simpson points out that the comprehensiveness and depth of the plan stood out most to him.

“It integrates everything from housing and heritage to tourism. It ticks a lot of boxes for our city’s initiatives, and it’s integrative to a number of other community planning initiatives we have on the go.”

“Creating a plan is very much a partnership. It’s not just planning. It’s not just landscape architecture. It’s a hybrid of all of the efforts that the team puts in, to allow for the creation of a plan intended to make significant changes to a place,” she says. “It is nice to have that effort appreciated by the Planning Institute.”

On what made the award-winning effort successful for the City, Mayor Simpson says it comes down to one simple thing: trust.

“When local governments can have the kind of partnership that we do with Urban, and with Shasta, I think you can just build a relationship that is seamless with something that fits the community. I don’t think the Waterfront Plan would have been as robust or as comprehensive without that pre-existing trust relationship that we had.”